It all began in 1838 at Fort Vancouver in Washington state with the arrival of Father Francis Norbert Blanchet and Father Modest Demers, priests of the Archdiocese of Quebec who came to the Oregon Country at the request of Dr. John McLoughlin, the chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company. McLoughlin was responding to the requests of his French Catholic employees for priests to serve their spiritual needs.

A year later, in 1839, at St. Paul (then called French Prairie), on the Feast of the Epiphany, twenty years before Oregon became a state (February 14, 1859), the first Mass in the Oregon Country was celebrated. As the population of Oregon Catholics increased, Rome, in 1843, established the Vicariate Apostolic of the Oregon Territory, with Francis Norbert Blanchet as the first vicar apostolic and bishop; then, to the surprise of many, in 1846, Pope Pius IX raised the vicariate to the dignity of an archdiocese, the Archdiocese of Oregon City, with Francis Norbert Blanchet as its first archbishop, and suffragan sees at Walla Walla and Vancouver Island. After the Archdiocese of Baltimore on the east coast, the Archdiocese of Oregon City (now Portland), is the second oldest archdiocese in the United States.

A year later, in 1839, at St. Paul (then called French Prairie), on the Feast of the Epiphany, twenty years before Oregon became a state (February 14, 1859), the first Mass in the Oregon Country was celebrated. As the population of Oregon Catholics increased, Rome, in 1843, established the Vicariate Apostolic of the Oregon Territory, with Francis Norbert Blanchet as the first vicar apostolic and bishop; then, to the surprise of many, in 1846, Pope Pius IX raised the vicariate to the dignity of an archdiocese, the Archdiocese of Oregon City, with Francis Norbert Blanchet as its first archbishop, and suffragan sees at Walla Walla and Vancouver Island. After the Archdiocese of Baltimore on the east coast, the Archdiocese of Oregon City (now Portland), is the second oldest archdiocese in the United States.

The Native Populations of the Oregon Territory at the Time of the Early Explorers, Settlers, and Missionaries

Before we actually get into the history, growth, and development of the Catholic Church in the Oregon Territory, it is important to say something about the native populations present at the time the early explorers, the fur traders, the settlers, and the missionaries arrived. How large and diverse were the native populations? And what word or name should we use to refer to these indigenous and native peoples?

To start with the question of naming: what should we call these peoples? What exonym is useful? Indians, Native Americans, American Indians, Indigenous Peoples, First Nation, Aboriginals? Tribal names? In fact, no single term is appropriate in all instances, and there is no agreement among scholars. This article will choose a name that seems best for the context as it moves through the various peoples and cultures.

The origins and timings of native peoples in the Oregon Territory are based on the ebb and flow of glaciers and the existence of a land bridge linking Asia with North America. Over thousands of years, first vegetation, then large mammals, and finally human hunters and gatherers moved onto and eventually crossed the land bridge. People slowly migrated southward, following a route along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains and, as growing evidence suggests, along the coast.

There is considerable evidence that humans have lived in the Pacific Northwest at least fifteen thousand years. Archeological evidence in the Fort Rock area (central Oregon), The Dalles, and on the Oregon Coast indicate that people were beginning to occupy several locations in the region ten thousand to five thousand years ago. In Oregon’s western valleys there is archeological evidence that humans were present from six thousand to ten thousand years ago.

In about 1800, before the ravages of Old World diseases dramatically reduced their numbers, a conservative estimate of the Native population of the Pacific Northwest was about 180,000 people. Some scholars increase this number, at the upper end, at about 300,000.

At some point during the 1770s and 1780s, the European voyagers to the North Pacific Coast introduced viruses and bacteria to people who had no immunological defenses against them. The consequences were catastrophic. It is estimated that there was a hemisphere-wide population decline of at least 90 percent in the centuries following the Columbian voyage of 1492.

Smallpox and other Old World diseases probably arrived relatively late on the Northwest Coast because the region was generally distant and beyond the major routes of European travel. The evidence suggests that, beginning in the mid-1770s, mariners from Spanish ships landing along the Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia coasts spread smallpox among the people they encountered. Studies indicate the spread of smallpox in the 1780s from the Tillamooks on the Oregon Coast to the Tlingits in the north. The disease caused profound social and cultural upheavals with mortality estimates in excess of thirty percent from the initial outbreaks.

Though we have no official written records when Lewis and Clark wintered on the lower Columbia River in 1805-6, they found that smallpox had already greatly reduced the population of local Clatsop villages. In fact, by the 1850s, tribes on the northwest coast lost an estimated 80% of their populations. The Siletz people alone lost 90% of their population in less than a century.

So, who were the people that inhabited the Oregon Coast at first contact with Euro-Americans? The Clatsop tribe lived around the mouth of the Columbia River. South of Tillamook Head were the Tillamook and the Nehalem Tillamook. Their homeland extended as far south as present-day Lincoln City. Further to the south were the Siletz, Yaquina, and Alsea peoples. The Kalapuya people resided in the foothills of the Cascade Range. The Siuslaw and the Lower Umpqua peoples lived from Heceta Head south to the dunes around present-day Reedsport. At Coos Bay were the Hanis Coos, the Miluk Coos, and Upper Coquille. South of them were the Coastal Rogue and the Chetco. The Chinook and the Kalapuya tribes largely populated the area from Portland into the Willamette Valley.

The Kalapuya tribe was the most numerous among the tribes inhabiting the Willamette Valley, with some bands living in the upper Umpqua Basin. During the transition of seasons, people in the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue valleys, and the Klamath and Modocs in the upper Klamath Basin, harvested camas, acorns, wapato (similar to potatoes), hazelnuts, arrowroot, tule, cattails, and many berry varieties. They also hunted deer, elk, waterfowl, and fished local streams for salmon and freshwater fish. Camas was the most widespread and important of the root bulbs.

With Thomas Jefferson’s election as president of the United States in 1800, forces were set in motion that initiated a great immigrant movement to the Pacific Northwest that eventually marginalized Native people in their own homelands.

Before we actually get into the history, growth, and development of the Catholic Church in the Oregon Territory, it is important to say something about the native populations present at the time the early explorers, the fur traders, the settlers, and the missionaries arrived. How large and diverse were the native populations? And what word or name should we use to refer to these indigenous and native peoples?

To start with the question of naming: what should we call these peoples? What exonym is useful? Indians, Native Americans, American Indians, Indigenous Peoples, First Nation, Aboriginals? Tribal names? In fact, no single term is appropriate in all instances, and there is no agreement among scholars. This article will choose a name that seems best for the context as it moves through the various peoples and cultures.

The origins and timings of native peoples in the Oregon Territory are based on the ebb and flow of glaciers and the existence of a land bridge linking Asia with North America. Over thousands of years, first vegetation, then large mammals, and finally human hunters and gatherers moved onto and eventually crossed the land bridge. People slowly migrated southward, following a route along the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains and, as growing evidence suggests, along the coast.

There is considerable evidence that humans have lived in the Pacific Northwest at least fifteen thousand years. Archeological evidence in the Fort Rock area (central Oregon), The Dalles, and on the Oregon Coast indicate that people were beginning to occupy several locations in the region ten thousand to five thousand years ago. In Oregon’s western valleys there is archeological evidence that humans were present from six thousand to ten thousand years ago.

In about 1800, before the ravages of Old World diseases dramatically reduced their numbers, a conservative estimate of the Native population of the Pacific Northwest was about 180,000 people. Some scholars increase this number, at the upper end, at about 300,000.

At some point during the 1770s and 1780s, the European voyagers to the North Pacific Coast introduced viruses and bacteria to people who had no immunological defenses against them. The consequences were catastrophic. It is estimated that there was a hemisphere-wide population decline of at least 90 percent in the centuries following the Columbian voyage of 1492.

Smallpox and other Old World diseases probably arrived relatively late on the Northwest Coast because the region was generally distant and beyond the major routes of European travel. The evidence suggests that, beginning in the mid-1770s, mariners from Spanish ships landing along the Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia coasts spread smallpox among the people they encountered. Studies indicate the spread of smallpox in the 1780s from the Tillamooks on the Oregon Coast to the Tlingits in the north. The disease caused profound social and cultural upheavals with mortality estimates in excess of thirty percent from the initial outbreaks.

Though we have no official written records when Lewis and Clark wintered on the lower Columbia River in 1805-6, they found that smallpox had already greatly reduced the population of local Clatsop villages. In fact, by the 1850s, tribes on the northwest coast lost an estimated 80% of their populations. The Siletz people alone lost 90% of their population in less than a century.

So, who were the people that inhabited the Oregon Coast at first contact with Euro-Americans? The Clatsop tribe lived around the mouth of the Columbia River. South of Tillamook Head were the Tillamook and the Nehalem Tillamook. Their homeland extended as far south as present-day Lincoln City. Further to the south were the Siletz, Yaquina, and Alsea peoples. The Kalapuya people resided in the foothills of the Cascade Range. The Siuslaw and the Lower Umpqua peoples lived from Heceta Head south to the dunes around present-day Reedsport. At Coos Bay were the Hanis Coos, the Miluk Coos, and Upper Coquille. South of them were the Coastal Rogue and the Chetco. The Chinook and the Kalapuya tribes largely populated the area from Portland into the Willamette Valley.

The Kalapuya tribe was the most numerous among the tribes inhabiting the Willamette Valley, with some bands living in the upper Umpqua Basin. During the transition of seasons, people in the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue valleys, and the Klamath and Modocs in the upper Klamath Basin, harvested camas, acorns, wapato (similar to potatoes), hazelnuts, arrowroot, tule, cattails, and many berry varieties. They also hunted deer, elk, waterfowl, and fished local streams for salmon and freshwater fish. Camas was the most widespread and important of the root bulbs.

With Thomas Jefferson’s election as president of the United States in 1800, forces were set in motion that initiated a great immigrant movement to the Pacific Northwest that eventually marginalized Native people in their own homelands.

Lewis and Clark arrived at the Pacific Ocean on November 7, 1805. The “corps” built Fort Clatsop and spent the winter there, returning to St. Louis in September 1806. When word of the fur trade in the Northwest reached the ears of John Jacob Astor, a New York merchant, he took an immediate interest. His first ship arrived at the mouth of the Columbia River in March 1811. His crew established the first American settlement in the Northwest, calling it Astoria. The stage was set for much change in the Oregon Country.

Dr. John McLoughlin: Father of Oregon

The fur trade continued to grow, and the Hudson’s Bay Company sent Dr. John McLoughlin (1784-1857) to Oregon in 1824 as its chief factor. Prior to this, in 1818, Great Britain and the United States agreed that, for a period of ten years, the citizens and subjects of each nation would have equal access to the Oregon country. This arrangement lasted until 1846, when the boundary between Canada and the United States was set at the 49th parallel.

Central to the history of this early period is Dr. McLoughlin, and he is rightly called the “Father of Oregon.” It was his decision to move the headquarters of the Hudson’s Bay Company from Astoria to Fort Vancouver, the confluence of the Columbia and the Willamette Rivers, in 1825. As one of the most powerful and influential people in Oregon history, McLoughlin also played an important role in the early history of Catholicism in the Pacific Northwest.

McLoughlin was described as a striking figure, with steel blue-grey eyes, a ruddy complexion, a tall muscular frame, and shoulder length white hair. As chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) in the Oregon Territory, McLoughlin looked after the HBC’s business interests in the Pacific Northwest. The district governor of the company, George Simpson, saw McLoughlin as a “man of strict honor and integrity, but a great stickler for rights and privileges,” with a turbulent disposition that sometimes led to conflict.

McLoughlin was born in Quebec, on October 19, 1784, to a family with both a Catholic and Protestant lineage. At a young age, McLoughlin desired a career in Medicine; and, after an apprenticeship with a Quebec physician, received a license to practice medicine in 1803. That same year, Loughlin joined the North West Company as surgeon and apprentice clerk. In 1810 or 1811, McLoughlin met Marguerite McKay, a (common law?) relationship that lasted until McLoughlin’s death.

McLoughlin’s connection to Oregon began in 1824, with the merger of the North West Company into the Hudson’s Bay Company. It was then that Loughlin was appointed chief factor of the Columbia Department, which encompassed all the land from the crest of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean. It would be McLoughlin’s responsibility to initiate a maritime coastal trade and to increase British presence between the Columbia River and the 49th parallel. McLoughlin was also to extract as much profit as possible from the region south and east of the Columbia River before it became American.

From Fort Vancouver, McLoughlin diversified the HBC, launching the first large-scale agricultural, lumber, and salmon export industries. He also empowered trapping brigades to extract as many furs as possible south of the Columbia. Of special note regarding the character of John McLoughlin, he was well known at the time for welcoming new settlers, especially missionaries, often lending them seed and grain.

It was John McLoughlin who, in the 1830s, persuaded retiring HBC employees to homestead in the Willamette Valley, realizing that it would not long remain without settlers. Preferring settlers that he and the HBC could influence, McLoughlin nurtured Euro-American communities in French Prairie (near present-day St. Paul).

his would lead to conflicts between Loughlin, the HBC, and the newly arriving Americans. Loughlin was known for his generosity in assisting Americans who were settling in the Willamette Valley with grain and seed and extended credit, to the dismay of the HBC. But McLoughlin also faced growing opposition from Americans who desired the HBC’s resources at Fort Vancouver and who resented McLoughlin’s land claims in Oregon City.

McLoughlin also faced false accusations of mistreatment of the Americans. In his defense of actions regarding Americans and HBC, McLoughlin said that if “he had refused them assistance, they would have starved, and the world would have raised a hue and cry against the company (HBC)... and they (the Americans) would as a last resort have taken Vancouver.”

The HBC wished to remove McLoughlin from his position, and they offered him to take a leave of absence in order to remain in Oregon—the legal requirement if he meant to hold his land claim in Oregon City—or to transfer to a position east of the Rocky Mountains. McLoughlin chose to stay in Oregon; and, in 1845, resigned from the British controlled HBC and built a house on his claim. The HBC allowed McLoughlin a furlough and leave of absence that extended (on paper) his HBC service to mid-1849.

In order to protect his land claims and to provide financial stability for his family, McLoughlin, in 1849, filed an intention to become a US citizen; and in 1851, he became one. Despite this, some businessmen continued to challenge McLoughlin, eventually passing legislation to deprive him of significant property holdings.

McLoughlin remained in Oregon City for the rest of his life. There, he managed his mercantile and milling interests, served briefly as the city’s mayor, and helped provision relief efforts following the murder of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in Walla Walla in 1847. McLoughlin died in his home in Oregon City on September 3, 1857.

As time passed after his death, American sentiment toward McLoughlin turned more positive, with many settlers to Oregon publicizing the support he provided them upon arrival. Today, McLoughlin’s house in Oregon City is preserved as the McLoughlin House Unit of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

Importantly for Oregon, and for the Catholic Church in Oregon, a statue of Dr. John McLoughlin is one of two statues (Jason Lee is the other) representing Oregon in The National Statuary Hall Collection in the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

As for John McLoughlin’s relationship with the Catholic Church, he was baptized Catholic in Quebec, Canada, but was raised Anglican. He returned to the Catholic Church in his later years. As mentioned, when the terms of some of his employees at the Hudson’s Bay Company expired, Dr. McLoughlin supplied them with provisions and farm implements and sent them into the Willamette Valley. They settled in a place called French Prairie, near the current town of St. Paul. These French Canadians were Catholic, and many had married native women. They longed for the sacraments of the Church, for marriage, and for the baptism of their children.

With that in mind, and at the request of these French-Canadian settlers, Dr. McLoughlin wrote to Bishop Joseph-Norbert Provencher in Winnipeg, Manitoba, in 1834 and 1835, asking that priests might be sent to those living in the Willamette Valley. The bishop said that he had no priests at Red River (Winnipeg) but that he would forward their petition to Archbishop Joseph Signay in Quebec. The archbishop ultimately decided to send two priests to the Oregon country, though the Hudson’s Bay Company objected to the establishment of a mission south of the Columbia River, whose sovereignty was disputed by the American and English governments. It was finally agreed by all parties that the original mission would be established north of the Columbia River, on the banks of the Cowlitz River (near present day Longview).

Father Francis Norbert Blanchet and Father Modeste Demers: Establishing the Mission at St. Paul

Eventually, Father Francis Norbert Blanchet was given charge of the mission at French Prairie (St. Paul) in Oregon, and he was appointed Vicar General to the archbishop of Quebec for the Oregon Country. Fr. Blanchet’s jurisdiction extended from the Rocky Mountains on the east to the Pacific Ocean on the west. Father Modeste Demers was appointed his assistant. The Catholic Church in the Northwest had begun.

It took Fr. Francis Norbert Blanchet and Fr. Modest Demers six months to travel from Montreal to Fort Vancouver. They arrived on Saturday, November 24, 1838. Dr. John McLoughlin was on a visit to Canada and England, so they were greeted by James Douglas, a governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company west of the Rocky Mountains. At the fort was a delegation of men representing the Canadians in the Willamette Valley. The following day, Sunday, Fr. Blanchet celebrated a High Mass at the fort—for many, the first celebration of Mass in ten or even twenty years, an emotional occasion bringing tears of joy.

A census taken at the time showed seventy-six Catholics at the fort, including a number of Catholic Iroquois. Fr. Blanchet wasted no time in getting his mission going, giving special attention to the spiritual needs of the native peoples. Father Demers had already learned the Chinook Jargon (a common language between the native peoples and Europeans, also called Chinuk Wawa), so he taught the Indians their prayers, which he had translated for them. He also taught about a hundred women and children who were preparing for Baptism. While Fr. Demers was with the Indians, Fr. Blanchet taught the catechism to the Canadians in both French and English (Blanchet was fluent in English from a previous assignment in New Brunswick). He also taught Gregorian Chant, and he took great pride that this chant was sung by both the Canadians and the Indians.

Though no mission was to be established south of the Columbia River, this did not stop Fr. Blanchet from attending to the spiritual needs of the Catholics in the Willamette Valley. On January 3, 1839, at the encouragement of Dr. McLoughlin, Fr. Blanchet set out for Champoeg. A colony of Catholic Canadians was established about four miles from there (near present day St. Paul). This was the community that had first petitioned Quebec for a priest. A church, the first erected in Oregon, was built in 1836—a log structure in anticipation of a priest. On January 6, 1839, a Sunday, and the Feast of the Epiphany, the church was blessed under the patronage of St. Paul; and Mass, for the first time in the future State of Oregon, was celebrated. Fr. Blanchet remained for four weeks in the community, instructing them, baptizing the women and children, and blessing marriages. There was confidence that, through the assistance of Dr. McLoughlin, a permanent mission would be established.

Of note at this time was a catechetical tool known as The Catholic Ladder, first used by Fr. Blanchet at the Cowlitz mission. The ladder would play an important role in catechizing the native peoples of Oregon and Washington. When word spread that a “black-gown” missionary had arrived at Cowlitz, delegations from northwest tribes came from remote distances to hear Fr. Blanchet. He explains the challenge in these words, “The great difficulty was to give them an idea of religion so plain and simple as to command their attention . . . and which they would carry back with them to their tribes.” This is where The Catholic Ladder came into play: a wooden board, about six feet long, with picture representations of the history of salvation. It proved quite successful.

Archbishop Francis Norbet Blanchet |  St. Paul Church, St. Paul, Oregon, Dedicated November 1, 1846, the oldest brick building in the Pacific Northwest |  Bishop Modeste Demers, first Bishop of Vancouver Island |

Rev. Pierre-Jean DeSmet, S.J.

Early Missionary Activity in the Pacific Northwest

The 1830s and 1840s saw a great deal of missionary activity in the Pacific Northwest. Sometimes the various denominations worked cooperatively to evangelize the native peoples, and sometimes not. The evidence is that as each group of missionaries arrived at Fort Vancouver, Dr. John McLoughlin offered them generous hospitality. Rev. Samuel Parker, a Presbyterian who arrived in 1835, said that Dr. McLoughlin “received me with many expressions of kindness and invited me to make his residence my home for the winter.” To the dismay of his superiors, Dr. McLoughlin was prodigal in offering food, supplies, and farm implements to the newly arrived settlers without any guarantee of repayment. Such displays of humanitarianism—especially with the American settlers—was unacceptable to his British HBC superiors, and it would ultimately lead to his resignation as chief factor. Dr. McLoughlin retired to Oregon City in 1846.

The first missionaries to arrive in the Oregon country were Methodists. Rev. Jason Lee and his nephew, Rev. Daniel Lee, arrived at Fort Vancouver in 1834. In 1836, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a mostly Congregationalist organization, sent Dr. Marcus Whitman and Rev. H. H. Spaulding to the northwest. Mrs. Whitman and Mrs. Spaulding made their home at Fort Vancouver for several months while the men were establishing their mission. Jason Lee had originally planned to set up a mission among the Flathead Indians (present day Montana), but Dr. McLoughlin advised against this and recommended that Lee settle in the nearby Willamette Valley. Lee eventually settled at a site a few miles northwest of present-day Salem. Here he met about a dozen French-Canadian settlers, with their wives and children. These Catholic families would later be served by Fr. Blanchet at St. Paul.

Though his work was mainly in eastern Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and the Upper-Midwest, mention should be made here of another great missionary: Fr. Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J. Fr. De Smet was a Belgian Jesuit priest who traveled to St. Louis in 1823 to complete his theological studies and to begin his studies of Native American languages. When a delegation came to St. Louis from the Flathead and Nez Perce Indians in search of “black robes,” they came into contact with Fr. De Smet. De Smet said that he had never met any Indians “so fervent in religion” as these delegates. In 1834, the Holy See gave care of the Indian missions to the Jesuits. Fr. De Smet volunteered his service, which was accepted; and, in March 1840, he headed for the Oregon Country.

As mentioned previously, the first Mass in the present-day State of Oregon took place at St. Paul (then called French Prairie) in 1839. Many missionaries arrived in the Oregon Country at this time, and Dr. John McLoughlin showed hospitality to all of them. His own inclination in religion was towards Catholicism. Already baptized Catholic, though raised Episcopalian, Dr. McLoughlin made his Profession of Faith on November 18, 1842. At Christmas Midnight Mass, he made his First Communion.

The 1830s and 1840s saw a great deal of missionary activity in the Pacific Northwest. Sometimes the various denominations worked cooperatively to evangelize the native peoples, and sometimes not. The evidence is that as each group of missionaries arrived at Fort Vancouver, Dr. John McLoughlin offered them generous hospitality. Rev. Samuel Parker, a Presbyterian who arrived in 1835, said that Dr. McLoughlin “received me with many expressions of kindness and invited me to make his residence my home for the winter.” To the dismay of his superiors, Dr. McLoughlin was prodigal in offering food, supplies, and farm implements to the newly arrived settlers without any guarantee of repayment. Such displays of humanitarianism—especially with the American settlers—was unacceptable to his British HBC superiors, and it would ultimately lead to his resignation as chief factor. Dr. McLoughlin retired to Oregon City in 1846.

The first missionaries to arrive in the Oregon country were Methodists. Rev. Jason Lee and his nephew, Rev. Daniel Lee, arrived at Fort Vancouver in 1834. In 1836, the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, a mostly Congregationalist organization, sent Dr. Marcus Whitman and Rev. H. H. Spaulding to the northwest. Mrs. Whitman and Mrs. Spaulding made their home at Fort Vancouver for several months while the men were establishing their mission. Jason Lee had originally planned to set up a mission among the Flathead Indians (present day Montana), but Dr. McLoughlin advised against this and recommended that Lee settle in the nearby Willamette Valley. Lee eventually settled at a site a few miles northwest of present-day Salem. Here he met about a dozen French-Canadian settlers, with their wives and children. These Catholic families would later be served by Fr. Blanchet at St. Paul.

Though his work was mainly in eastern Oregon, Idaho, Montana, and the Upper-Midwest, mention should be made here of another great missionary: Fr. Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J. Fr. De Smet was a Belgian Jesuit priest who traveled to St. Louis in 1823 to complete his theological studies and to begin his studies of Native American languages. When a delegation came to St. Louis from the Flathead and Nez Perce Indians in search of “black robes,” they came into contact with Fr. De Smet. De Smet said that he had never met any Indians “so fervent in religion” as these delegates. In 1834, the Holy See gave care of the Indian missions to the Jesuits. Fr. De Smet volunteered his service, which was accepted; and, in March 1840, he headed for the Oregon Country.

As mentioned previously, the first Mass in the present-day State of Oregon took place at St. Paul (then called French Prairie) in 1839. Many missionaries arrived in the Oregon Country at this time, and Dr. John McLoughlin showed hospitality to all of them. His own inclination in religion was towards Catholicism. Already baptized Catholic, though raised Episcopalian, Dr. McLoughlin made his Profession of Faith on November 18, 1842. At Christmas Midnight Mass, he made his First Communion.

The Importance of the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail made an enormous contribution to the population and culture of the Pacific Northwest while, at the same time, bringing prosperity and development to the future states. The trail extended roughly 2,000 miles from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon City on the Willamette River. By the time the railroads arrived in the 1860s and 1870s, 400,000 people had traveled the trail (and its tributaries) to the Oregon Country and to the greater West beyond.

Aside from trappers and early merchants, the missionaries were the first to traverse a path from the east coast to the west coast. Marcus Whitman was among the first, who, in 1835, set out to demonstrate that the westward trail to Oregon could be traveled safely. Returning to the east, Whitman set out again, now with his new bride, Narcissa. They went further west than Whitman’s first trip, using Indian trails to cross the Rockies, and finally reaching Fort Walla Walla and Fort Vancouver in 1836.

The western passage of emigrants began in 1839 when a small group of men departed Peoria, Illinois, with the intention of colonizing the Oregon Country. In 1840, Joseph Meek and Robert Newall, formerly fur trappers and mountain men, headed west. Their wagons were the first to reach the Columbia River overland, opening the final leg of the Oregon Trail to wagon traffic. In 1841, the Bartleson-Bidwell Party was the first emigrant group to attempt a wagon crossing from Missouri to the west (half the group headed for California).

The number of emigrants greatly expanded in 1843. Called “The Great Migration of 1843,” nearly 1,000 people, 120 wagons, and thousands of livestock left for Oregon on May 22nd. When the emigrants were told to leave their wagons at Fort Hall (near Pocatello, Idaho) and use pack animals, Marcus Whitman (who had joined the group) disagreed and volunteered to lead the wagons to Oregon. The biggest obstacle was the Blue Mountains, where they had to clear a path through thick forest. At The Dalles, the wagons had to be taken apart and floated down the hazardous Columbia River. They arrived in the Willamette Valley in October. The Barlow Road was constructed around Mt. Hood in 1846, providing a rough but passable trail to the Willamette Valley.

The covered wagon (a prairie schooner) was the single most important component for a successful trip along the Oregon Trail. It was also necessary to depart in April or May in order to arrive in Oregon before the winter snows. Once the settlers arrived, the Organic Laws of Oregon (the Provisional Government of Oregon, 1843) granted 640 acres (at no cost) to married couples and 320 acres to an unmarried settler. As the years passed, the Oregon Trail became a heavily used corridor between Missouri and the Columbia River. With the building of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, the heyday of the Oregon Trail had come to an end.

The Political Situation in 1840s Oregon and Joseph Lane, the First Governor of the Oregon Territory

As mentioned, the political situation in the Oregon Country was somewhat unsettled. A treaty in 1818, and later renewed, granted a joint occupancy of the Oregon Country by the United States and Great Britain. In the meanwhile, attempts were made to establish a local government that would bring greater order and stability to the increasing number of settlers. At the time, the settlers were not equally protected by the law. The English Parliament (through the Hudson’s Bay Company) had extended the civil laws of Canada to British subjects in the area; but there was no such provision for the Americans. Discussions began in 1841on the establishment of a government in the Oregon Country, though the Canadians were cool to the idea, fearing the loss of their protected status. Those promoting a provisional government were equally in opposition to the British Hudson’s Bay Company, which had taken on both governmental and police duties in the area. Fr. Blanchet was conflicted, since the establishment of a provisional government (American?) could easily affect his relationship with Dr. John McLoughlin, the chief factor of the British Hudson’s Bay Company. The question of jurisdiction, and American sovereignty, was ultimately resolved pragmatically by the influx of American settlers over the Oregon Trail. Personally, though not officially, Dr. McLoughlin did support the idea of a provisional government. But no matter his thoughts and motivations, Dr. McLoughlin’s first priority was to assist the emigrants who came west—at some cost to himself—no matter their nationality or background.

Fr. Blanchet’s attitude toward the establishment of a provisional government is disputed by Oregon historians. It is surmised that Fathers Blanchet and Demers’ British nationality prevented them from fully supporting the notion of a local government, but Fr. Blanchet himself denies this. He says that any perceived opposition on his part was a matter of timing and prudence. Whatever the facts might be, Father Blanchet participated in the early discussions (1841) regarding local governance, and he remained a respected leader in the Oregon community.

The vote for a Provisional Government took place on May 2, 1843. The male settlers of the Willamette Valley gathered at Champoeg to cast their ballot. The count showed 52 for the Provisional Government of Oregon and 50 against. This government provided a legal system and a common defense among the mostly American pioneers settling an area then inhabited by the many indigenous Nations. The laws were intended from the start as an interim entity until “whenever such time as the United States of America extends her jurisdiction over us.”

Though the Oregon Treaty of 1846 settled the border dispute between the United States and Canada (and Great Britain) at the 49th parallel, the Provisional Government continued until 1849, when the first governor of the Territory of Oregon (1848-1859) arrived.

On August 14, 1848, the United States Congress approved the formation of the Oregon Territory. At the time, the Oregon Territory included all of the present-day states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and parts of Montana and Wyoming. Its capital city was located at Oregon City. This vast, new territory had a sparse population of American settlers; two years later, the census of 1850 counted only 13,294 residents in the Oregon Territory.

The formation of Oregon came at a time of rapid expansion under President James Polk and his administration, which centered on Manifest Destiny and territorial growth in its domestic and foreign policy. On February 2, 1848, the United States and Mexico signed a treaty that ended the Mexican-American War. In the treaty, Mexico surrendered all of the states of California, Nevada, Utah, most of Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico.

One of the heroes of the Mexican-American War was Joseph Lane, born in North Carolina (1801). President Polk appointed Lane as first governor of the Oregon Territory on August 18, 1848, and he arrived in Oregon City on March 2, 1849. Lane was an active but controversial leader who made a strong impact on territorial politics. He dealt strongly with the Native Americans, gaining local popularity by obtaining the surrender of five Cayuse accused of murdering Marcus Whitman and his family. The five men were tried and hanged by territorial officials. In 1851, Lane won the first of the four-year terms as Oregon’s territorial delegate to Congress, eventually becoming an important part of the Oregon Democratic Party machine.

One of the most divisive issues at the time for Oregon voters was the issue of slavery. With a nod to his Southern background, Lane was convinced of the slaveholders’ right to bring slaves into any territory. When Oregon achieved statehood on February 14, 1859, Lane was elected to the U.S. Senate. Though Lane’s influence in Oregon remained strong, he alienated an increasing number of Oregonians as he continued to defend territorial slavery. When Abraham Lincoln became president in 1861, Lane rejected compromise and defended the secession of the South from the Union. With that, he ended his term in the Senate and retired from Oregon politics. He died in Roseburg, Oregon, on April 19, 1881.

Meanwhile, the Catholic community in Oregon was also looking to organize. Within a year of arriving in the Oregon Country, Fr. Blanchet saw the need and usefulness of having a bishop on the lower Columbia River. When Father De Smet came to St. Paul in 1842 to meet Father Blanchet, a principal topic of discussion was the establishment of a diocese.

The Organization of the Catholic Church in the Oregon Country

Shortly after Fr. Blanchet arrived in the Oregon Country in 1838, he saw the need for a bishop to serve the settlers in the far-flung missions of the Northwest. Ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the missions was not at all clear. By the Treaty of 1818, the United States and Great Britain agreed to joint occupancy of the Oregon Country. Fr Blanchet had been sent by the Bishop of Quebec, whose jurisdiction extended to the Rocky Mountains. The Diocese of St. Louis was established in 1826, and its jurisdiction was probably the same. There was one archdiocese in the United States at the time, Baltimore, so the Oregon Country would have been included in its ecclesiastical province. Yet, Fr. Blanchet was a vicar general of the Bishop of Quebec, serving mostly French-Canadian Catholics in the Willamette Valley of the Northwest.

In a letter to the Bishop of Quebec dated March 19, 1840, Fr. Blanchet recommended that an auxiliary bishop of Quebec be sent to Fort Vancouver. Later, in 1842, when Fr. De Smet, S.J., came to St. Paul, he and Fr. Blanchet discussed the possibility of a diocese in the Oregon Country. Fr. De Smet presented these ideas and recommendations to church authorities in St. Louis, his home base. At the same time, Fr. Blanchet wrote to Bishop Signay in Quebec and to Bishop Rosati in St. Louis, urging their collaboration in providing governance and spiritual care (i.e., a bishop) for the missions in Oregon. Fr. Blanchet recommended Fr. De Smet for bishop. Fr. Blanchet considered himself unfit for the office.

The Canadian and American bishops did collaborate in petitioning Rome for the establishment of church governance in the lower Columbia region, but each made a different request. The Canadian church recommended that a diocese be established, with Fr. Blanchet as bishop. American auxiliary bishop Peter Kenrick of St. Louis proposed the establishment of a vicariate apostolic (a first step in becoming a diocese) with Father De Smet as vicar apostolic. Rome compromised; and, on December 1, 1843, a vicariate apostolic was erected with Fr. Blanchet as vicar apostolic. Word of this decision did not reach Oregon until November 4, 1844. Bishop-Elect Blanchet decided to go to Canada for his episcopal ordination, crossing the bar of the Columbia River on December 5, 1844. It was a long trip: first to Honolulu, then around Cape Horn to England, doubling back from Liverpool to Boston, and finally arriving in Montreal towards the end of June 1845. On July 25th, Fr. Blanchet was ordained a bishop for the Oregon Country.

As Bishop-Elect Blanchet departed Oregon for his ordination, he reflected on his ministry in these words: “At the end of 1844, after six years of efforts disproportioned to the needs of the country, the vast mission of Oregon, on the eve of being erected into a vicariate apostolic, had gained nearly all of the Indian tribes, . . . it had brought six thousand pagans to the faith, . . . nine missions had been founded, and eleven churches and chapels had been erected.” For Fr. Francis Norbert Blanchet, the church, under his mission authority and work, was built on solid rock, and it continued to grow in the Oregon Country.

Shortly after Fr. Blanchet arrived in the Oregon Country in 1838, he saw the need for a bishop to serve the settlers in the far-flung missions of the Northwest. Ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the missions was not at all clear. By the Treaty of 1818, the United States and Great Britain agreed to joint occupancy of the Oregon Country. Fr Blanchet had been sent by the Bishop of Quebec, whose jurisdiction extended to the Rocky Mountains. The Diocese of St. Louis was established in 1826, and its jurisdiction was probably the same. There was one archdiocese in the United States at the time, Baltimore, so the Oregon Country would have been included in its ecclesiastical province. Yet, Fr. Blanchet was a vicar general of the Bishop of Quebec, serving mostly French-Canadian Catholics in the Willamette Valley of the Northwest.

In a letter to the Bishop of Quebec dated March 19, 1840, Fr. Blanchet recommended that an auxiliary bishop of Quebec be sent to Fort Vancouver. Later, in 1842, when Fr. De Smet, S.J., came to St. Paul, he and Fr. Blanchet discussed the possibility of a diocese in the Oregon Country. Fr. De Smet presented these ideas and recommendations to church authorities in St. Louis, his home base. At the same time, Fr. Blanchet wrote to Bishop Signay in Quebec and to Bishop Rosati in St. Louis, urging their collaboration in providing governance and spiritual care (i.e., a bishop) for the missions in Oregon. Fr. Blanchet recommended Fr. De Smet for bishop. Fr. Blanchet considered himself unfit for the office.

The Canadian and American bishops did collaborate in petitioning Rome for the establishment of church governance in the lower Columbia region, but each made a different request. The Canadian church recommended that a diocese be established, with Fr. Blanchet as bishop. American auxiliary bishop Peter Kenrick of St. Louis proposed the establishment of a vicariate apostolic (a first step in becoming a diocese) with Father De Smet as vicar apostolic. Rome compromised; and, on December 1, 1843, a vicariate apostolic was erected with Fr. Blanchet as vicar apostolic. Word of this decision did not reach Oregon until November 4, 1844. Bishop-Elect Blanchet decided to go to Canada for his episcopal ordination, crossing the bar of the Columbia River on December 5, 1844. It was a long trip: first to Honolulu, then around Cape Horn to England, doubling back from Liverpool to Boston, and finally arriving in Montreal towards the end of June 1845. On July 25th, Fr. Blanchet was ordained a bishop for the Oregon Country.

As Bishop-Elect Blanchet departed Oregon for his ordination, he reflected on his ministry in these words: “At the end of 1844, after six years of efforts disproportioned to the needs of the country, the vast mission of Oregon, on the eve of being erected into a vicariate apostolic, had gained nearly all of the Indian tribes, . . . it had brought six thousand pagans to the faith, . . . nine missions had been founded, and eleven churches and chapels had been erected.” For Fr. Francis Norbert Blanchet, the church, under his mission authority and work, was built on solid rock, and it continued to grow in the Oregon Country.

From Vicariate Apostolic to the Archdiocese of Oregon City

Father Francis Norbert Blanchet was ordained a bishop in Montreal on July 25, 1845. He had already been gone seven months from Oregon; but instead of returning to his vicariate, he decided instead to travel to Europe. His purpose was to inform Rome of his mission territory; seek additional bishops, priests, and religious women to serve with him; and to collect funds to build churches and schools in the vast Oregon Country.

Bishop Blanchet’s first stop was Belgium, where he recruited Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur (he received seven) and roused interest in his mission territory. He then headed for Rome, arriving January 5, 1846. He received an audience with Pope Gregory XVI, who invited him to another meeting to discuss the needs of his distant vicariate. Because of his warm reception at the Vatican, and on the advice of influential friends in Rome, Bishop Blanchet boldly requested the establishment of an ecclesiastical province in the distant Pacific Northwest. The request was bold because it meant that the United States would receive a second archdiocese with a second archbishop—not New York or Philadelphia or St. Louis, but a lowly vicariate apostolic in a part of the country that was not yet even a United States territory.

Bishop Blanchet made his proposal to the Congregation of the Propaganda Fide (now called the "Dicastery for Evangelization,” the missionary wing of the Holy See). He must have been very convincing because, by a decree of the newly-elected Pope Pius IX, dated July 2, 1846, the vicariate apostolic was elevated to an ecclesiastical province with Oregon City as the archdiocesan see, and Walla Walla and Vancouver Island as its suffragan sees. Bishop Blanchet became Archbishop of Oregon City; Fr. Modeste Demers became Bishop of Vancouver Island; and Father A. M. A. Blanchet, brother of Archbishop Blanchet and a priest of Montreal, became Bishop of Walla Walla.

Bishop Blanchet remained in Rome for four months, departing on May 8, 1846. His travels took him to Prussia, Bavaria, Cologne, Bonn, Munich, Vienna, and finally, Paris. It was in Paris that Bishop Blanchet learned of his promotion to the Metropolitan See of Oregon City. His travels through Europe resulted in many donations for the missions in Oregon, and he finally departed Europe on February 22, 1847. Six months later, on August 19, 1847, his ship arrived at the mouth of the Willamette River. He had been away from Oregon almost three years. On August 25, 1847, Archbishop Blanchet arrived at his “cathedral” in Oregon City, where he celebrated Mass and sang a Te Deum (“Te Deum laudamus,” meaning, “We praise thee, O God”) in gratitude for his successful and safe travel.

The Whitman Massacre and the California Gold Rush

Bishop Augustin Blanchet

Bishop Augustin BlanchetThe Whitman Massacre took place on November 29, 1847. Dr. Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa, both Protestant missionaries, were attacked by Cayuse Indians near the confluence of the Columbia and the Walla Walla Rivers. Twelve others were killed with them, and 53 (mostly) women and children were taken hostage. A nearby Catholic mission was also affected by this massacre. Bishop Augustin Blanchet, the newly appointed Bishop of Walla Walla, found it necessary to leave the troubled area and take refuge with his brother, Archbishop Francis Norbert Blanchet, in St. Paul and Oregon City. The brutal massacre had far reaching effects, not only for missionary work in Oregon, but also in the relationship of the native peoples to the US government, the difficult passage of the pioneers along the Oregon Trail, the early rise of anti-Catholicism in Oregon, and the formation of Indian reservations in the Pacific Northwest.

Meanwhile, the Catholic missions at St. Paul and Oregon City continued to grow. A school for boys, St. Joseph’s College, opened in St. Paul in 1843. In the same year (then) Fr. Blanchet accompanied Dr. McLoughlin to Oregon City where a site was chosen for the Catholic church (the present-day location of St. John’s Church). Fr. Pierre DeSmet returned from Europe in 1844 and brought with him six Sisters of Notre Dame de Namur and four Jesuit priests. The Jesuits founded St. Francis Xavier mission, about a mile west of St. Paul. The sisters staffed a girl’s academy. The Jesuit mission, which was the headquarters of the Jesuits, closed after five years because of its distance from the other Jesuit missions. The sisters would open a second school at Oregon City in 1848.

The following year, 1849, would prove to be challenging for the Catholic missions. Gold was discovered in California, and gold fever hit the Catholic population in Oregon. In May of 1849, many families at French Prairie departed for the California gold fields. St. Joseph’s College at St. Paul closed in June 1849 for lack of students. The Sisters of Notre Dame closed the girls’ academy in 1852. The population of Oregon City also declined, for both political and economic reasons. Because of this, in 1853, the Notre Dame sisters had to close the only remaining Catholic school in the Oregon country.

Archbishop Blanchet returned from Europe on August 25, 1847, bringing with him three more Jesuit priests, five diocesan priests, and seven Notre Dame sisters. He then began to organize the administration of his vast archdiocese.

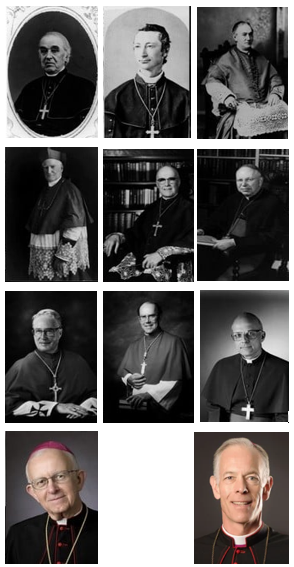

The Founders of the Catholic Church in the Oregon Territory: (left to right) Bishop Agustin-Magloire A. Blanchet, Archbishop Francis Norbert Blanchet, and Bishop Modeste Demers, c. 1848

The Organization of the new Archdiocese of Oregon City

It was the responsibility of Archbishop Blanchet to organize his vast archdiocese, now including two suffragan sees, at Walla Walla and Vancouver Island. Archbishop Blanchet’s brother, Fr. Augustin Magloire Alexandre Blanchet (A.M.A. Blanchet), was ordained Bishop of Walla Walla in Montreal on September 27, 1846, and he arrived at Fort Walla Walla after a five-month journey by way of St. Louis. The bishop established his Catholic mission a short distance from that of Dr. Marcus Whitman at Walla Walla. While this was taking place, Archbishop Blanchet was preparing to ordain Fr. Modeste Demers as the new bishop of Vancouver Island, and his consecration took place at St. Paul on November 30, 1847. There was optimism and hope regarding the Catholic missions of the territory.

But the Whitman Massacre of November 29, 1847, changed everything. The massacre would have far-reaching effects on the missionary activity in Oregon, and it precipitated the first stirrings of anti-Catholicism in the territory (Catholics were falsely accused of inciting the Whitman Massacre and the consequent Cayuse War of 1847 to 1855). The troubles escalated to the point that a petition was sent to the Territorial Legislature in 1848 to expel Catholic clergy from Oregon. Fortunately, reasonable heads prevailed, and the petition was dropped.

As a result of the Whitman Massacre, the Catholic mission at Walla Walla was closed, and Bishop A.M.A. Blanchet took refuge with his brother at Oregon City and St. Paul. To deal with the challenge to the missions, and other administrative issues of the territory, Archbishop Blanchet called a council, the First Provincial Council of Oregon on February 27, 1848, at St. Paul. Bishop Demers was still in St. Paul, so it gave the three bishops the opportunity to review the needs of the territory and to plan for its future.

Bishop Demers was selected to take the various provincial council documents to Rome for approval, but political troubles in Europe, and especially in Italy and Rome, delayed his travels for over a year. Instead, he headed to his new diocese, the Diocese of Vancouver Island. He was the only priest in the entire diocese; thus, his trip to Europe would also be a call for missionaries and for the financial support of his distant mission. He did not return to his diocese until August 20, 1852.

At the same time, Bishop A.M.A. Blanchet wanted to return to his diocese at Walla Walla in 1848, but he was detained at The Dalles by the Superintendent of Indian Affairs. The relations between the white settlers and the native peoples were too dangerous to allow passage. Bishop Blanchet thus remained at The Dalles and established St. Peter Mission, where he remained until 1850.

As a result of a request from the First Provincial Council, a letter arrived from Rome, dated May 31, 1850, creating a new diocese at Nesqually (later spelled “Nisqually, now the Archdiocese of Seattle) and transferring the bishop of Walla Walla, Bishop Blanchet, to this new see. In addition, the Diocese of Walla Walla was suppressed. The church in the northwest was beginning to take shape.

It was the responsibility of Archbishop Blanchet to organize his vast archdiocese, now including two suffragan sees, at Walla Walla and Vancouver Island. Archbishop Blanchet’s brother, Fr. Augustin Magloire Alexandre Blanchet (A.M.A. Blanchet), was ordained Bishop of Walla Walla in Montreal on September 27, 1846, and he arrived at Fort Walla Walla after a five-month journey by way of St. Louis. The bishop established his Catholic mission a short distance from that of Dr. Marcus Whitman at Walla Walla. While this was taking place, Archbishop Blanchet was preparing to ordain Fr. Modeste Demers as the new bishop of Vancouver Island, and his consecration took place at St. Paul on November 30, 1847. There was optimism and hope regarding the Catholic missions of the territory.

But the Whitman Massacre of November 29, 1847, changed everything. The massacre would have far-reaching effects on the missionary activity in Oregon, and it precipitated the first stirrings of anti-Catholicism in the territory (Catholics were falsely accused of inciting the Whitman Massacre and the consequent Cayuse War of 1847 to 1855). The troubles escalated to the point that a petition was sent to the Territorial Legislature in 1848 to expel Catholic clergy from Oregon. Fortunately, reasonable heads prevailed, and the petition was dropped.

As a result of the Whitman Massacre, the Catholic mission at Walla Walla was closed, and Bishop A.M.A. Blanchet took refuge with his brother at Oregon City and St. Paul. To deal with the challenge to the missions, and other administrative issues of the territory, Archbishop Blanchet called a council, the First Provincial Council of Oregon on February 27, 1848, at St. Paul. Bishop Demers was still in St. Paul, so it gave the three bishops the opportunity to review the needs of the territory and to plan for its future.

Bishop Demers was selected to take the various provincial council documents to Rome for approval, but political troubles in Europe, and especially in Italy and Rome, delayed his travels for over a year. Instead, he headed to his new diocese, the Diocese of Vancouver Island. He was the only priest in the entire diocese; thus, his trip to Europe would also be a call for missionaries and for the financial support of his distant mission. He did not return to his diocese until August 20, 1852.

At the same time, Bishop A.M.A. Blanchet wanted to return to his diocese at Walla Walla in 1848, but he was detained at The Dalles by the Superintendent of Indian Affairs. The relations between the white settlers and the native peoples were too dangerous to allow passage. Bishop Blanchet thus remained at The Dalles and established St. Peter Mission, where he remained until 1850.

As a result of a request from the First Provincial Council, a letter arrived from Rome, dated May 31, 1850, creating a new diocese at Nesqually (later spelled “Nisqually, now the Archdiocese of Seattle) and transferring the bishop of Walla Walla, Bishop Blanchet, to this new see. In addition, the Diocese of Walla Walla was suppressed. The church in the northwest was beginning to take shape.

The Catholic Church in the Oregon Territory and the Challenges of the 1850s

The Catholic Church in Oregon was beginning to take shape in the 1840s. The First Provincial Council of Oregon City took place in 1848, and bishops were assigned to the Dioceses of Vancouver Island (Bishop Demers) and the newly erected Diocese of Nesqually (Bishop A.M.A. Blanchet [later spelled “Nisqually,” now the Archdiocese of Seattle]). But things are never easy, and the 1850s proved to be a challenging time for Archbishop Blanchet and his local church.

First of all, establishing the missions in St. Paul and Oregon City generated a great deal of debt. Had the mission population continued to grow in pace, this might not have been a problem. One might say that the missions were “overbuilt,” that is, they were built with the hope that the population would continue to grow. As it was, the conditions of the 1850s were such that the population declined, partially because of the gold rush and also because of the appropriation of land belonging to Dr. John McLoughlin in Oregon City. Local officials appropriated this land for a university, but Dr. McLoughlin’s intent was for commerce and housing. Newly arriving pioneers looked beyond Oregon City and moved to other settlements in the Willamette Valley. A visitor from France who spent time with Archbishop Blanchet in Oregon City described the sorry sight of the “’archepiscopal palace’ as worthy of John the Baptist.” Given the financial situation of the archdiocese, this estimation was probably an understatement.

Though the leadership of Archbishop Blanchet was needed in Oregon, he decided to make a tour of South America to seek funds for his ailing archdiocese. He left Oregon City in the fall of 1855, and he headed to the far south, spending some time in Peru and Bolivia. His efforts were particularly successful in Chile, where he published a Spanish monograph on the history of his ecclesiastical province in the northwest. Archbishop Blanchet included in this sketch the many misfortunes that had befallen his archdiocese and the settlers, and he asked for help to rebuild this local church. With funds in hand, Archbishop Blanchet returned to Oregon in December 1857, two years later, ready to meet the debts and to serve the spiritual needs of his missionary archdiocese.

But money wasn’t the only problem for the missions in Oregon. A report on the state of the archdiocese in 1855-56 gives indication of the trying circumstances. The schools had all closed. All the religious priests and sisters had departed. Archbishop Blanchet was absent from the archdiocese for two years, seeking funds in South America. The number of diocesan clergy decreased from 19 to 7. Missions that were once thriving were now vacant. Work among the native peoples was suspended. Anti-Catholic fervor and bigotry increased. The population of Oregon City continued to decline. From a historical standpoint, this was a low point in the early Catholic history of Oregon.

Even as Oregon City was declining, a settlement downriver was beginning to grow: Portland. In 1851, Archbishop Blanchet authorized Fr. James Croke to solicit funds for a new church. The future was beginning to emerge, and there was optimism in the air.

The Catholic Church in Oregon was beginning to take shape in the 1840s. The First Provincial Council of Oregon City took place in 1848, and bishops were assigned to the Dioceses of Vancouver Island (Bishop Demers) and the newly erected Diocese of Nesqually (Bishop A.M.A. Blanchet [later spelled “Nisqually,” now the Archdiocese of Seattle]). But things are never easy, and the 1850s proved to be a challenging time for Archbishop Blanchet and his local church.

First of all, establishing the missions in St. Paul and Oregon City generated a great deal of debt. Had the mission population continued to grow in pace, this might not have been a problem. One might say that the missions were “overbuilt,” that is, they were built with the hope that the population would continue to grow. As it was, the conditions of the 1850s were such that the population declined, partially because of the gold rush and also because of the appropriation of land belonging to Dr. John McLoughlin in Oregon City. Local officials appropriated this land for a university, but Dr. McLoughlin’s intent was for commerce and housing. Newly arriving pioneers looked beyond Oregon City and moved to other settlements in the Willamette Valley. A visitor from France who spent time with Archbishop Blanchet in Oregon City described the sorry sight of the “’archepiscopal palace’ as worthy of John the Baptist.” Given the financial situation of the archdiocese, this estimation was probably an understatement.

Though the leadership of Archbishop Blanchet was needed in Oregon, he decided to make a tour of South America to seek funds for his ailing archdiocese. He left Oregon City in the fall of 1855, and he headed to the far south, spending some time in Peru and Bolivia. His efforts were particularly successful in Chile, where he published a Spanish monograph on the history of his ecclesiastical province in the northwest. Archbishop Blanchet included in this sketch the many misfortunes that had befallen his archdiocese and the settlers, and he asked for help to rebuild this local church. With funds in hand, Archbishop Blanchet returned to Oregon in December 1857, two years later, ready to meet the debts and to serve the spiritual needs of his missionary archdiocese.

But money wasn’t the only problem for the missions in Oregon. A report on the state of the archdiocese in 1855-56 gives indication of the trying circumstances. The schools had all closed. All the religious priests and sisters had departed. Archbishop Blanchet was absent from the archdiocese for two years, seeking funds in South America. The number of diocesan clergy decreased from 19 to 7. Missions that were once thriving were now vacant. Work among the native peoples was suspended. Anti-Catholic fervor and bigotry increased. The population of Oregon City continued to decline. From a historical standpoint, this was a low point in the early Catholic history of Oregon.

Even as Oregon City was declining, a settlement downriver was beginning to grow: Portland. In 1851, Archbishop Blanchet authorized Fr. James Croke to solicit funds for a new church. The future was beginning to emerge, and there was optimism in the air.

The First Mass in Portland, and the Arrival of the Missionary Sisters

The first Mass in Portland was celebrated in an unfinished church in the vicinity of Fifth and Couch Streets on Christmas Eve, 1851. Two months later, on February 22, 1852, the church was dedicated by Archbishop Blanchet. Because of its “remote location” in the city, the church was moved in 1854 to Third and Stark Street.

The Catholic population of Oregon was beginning to grow, though slowly. Fr. James Croke took an informal census of Catholics in 1853-54 as he traveled north and south through the archdiocese, concentrating on three areas: Rogue River, Umpqua River, and the Willamette Valley. He reported that the total number of Catholics, adults and minors, was 303.

Archbishop Blanchet returned to Oregon from his fundraising efforts in South America in 1857. The Catholic population was beginning to recover from the gold rush losses, and the archbishop turned his attention to Catholic education. His brother, Bishop Blanchet of Nesqually, had already secured the assistance of the Sisters of Providence in Montreal, who made a foundation in Vancouver, Washington. Bishop Demers on Vancouver Island requested that the newly formed Sisters of St. Anne in Quebec establish a convent at Victoria to serve the educational needs of both the European settlers and the native populations.

Like his brother bishops, Archbishop Blanchet looked to French Canada for religious to staff his schools. After securing property in Portland for a school and convent, Blanchet headed to Montreal. With the assistance of Archbishop Bourget, who consecrated him in 1845, Archbishop Blanchet made contact with the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary who agreed to come west. Twelve sisters, with their superior, Mother Alphonse, left Montreal and arrived in Portland on October 21, 1859. They established St. Mary’s Academy at its present location in the city, and a great tradition of education was born. The academy opened on November 6, 1859, with six pupils. Towards the end of November, they opened a class for boys. The sisters would go on to establish schools in Oregon City (1860), St. Paul (1861), Salem (1863), The Dalles (1864), and Jacksonville (1865). In many ways, education and medicine are the legacy of the Catholic Church in the pioneer territories of the Pacific Northwest—virtually all provided by religious women.

Mention must be made of one outstanding religious woman, Mother Joseph Pariseau, S.P., of the Sisters of Providence. At the invitation of Bishop Blanchet of Nesqually, Mother Joseph and four other sisters headed west and arrived in Vancouver, Washington, on December 8, 1856. Despite enormous hardships, Mother Joseph established more than 30 hospitals, schools, and homes for orphans and the elderly throughout Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana. To honor her, the State of Washington chose Mother Joseph as one of two statues to be placed in Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C.

The first Mass in Portland was celebrated in an unfinished church in the vicinity of Fifth and Couch Streets on Christmas Eve, 1851. Two months later, on February 22, 1852, the church was dedicated by Archbishop Blanchet. Because of its “remote location” in the city, the church was moved in 1854 to Third and Stark Street.

The Catholic population of Oregon was beginning to grow, though slowly. Fr. James Croke took an informal census of Catholics in 1853-54 as he traveled north and south through the archdiocese, concentrating on three areas: Rogue River, Umpqua River, and the Willamette Valley. He reported that the total number of Catholics, adults and minors, was 303.

Archbishop Blanchet returned to Oregon from his fundraising efforts in South America in 1857. The Catholic population was beginning to recover from the gold rush losses, and the archbishop turned his attention to Catholic education. His brother, Bishop Blanchet of Nesqually, had already secured the assistance of the Sisters of Providence in Montreal, who made a foundation in Vancouver, Washington. Bishop Demers on Vancouver Island requested that the newly formed Sisters of St. Anne in Quebec establish a convent at Victoria to serve the educational needs of both the European settlers and the native populations.

Like his brother bishops, Archbishop Blanchet looked to French Canada for religious to staff his schools. After securing property in Portland for a school and convent, Blanchet headed to Montreal. With the assistance of Archbishop Bourget, who consecrated him in 1845, Archbishop Blanchet made contact with the Sisters of the Holy Names of Jesus and Mary who agreed to come west. Twelve sisters, with their superior, Mother Alphonse, left Montreal and arrived in Portland on October 21, 1859. They established St. Mary’s Academy at its present location in the city, and a great tradition of education was born. The academy opened on November 6, 1859, with six pupils. Towards the end of November, they opened a class for boys. The sisters would go on to establish schools in Oregon City (1860), St. Paul (1861), Salem (1863), The Dalles (1864), and Jacksonville (1865). In many ways, education and medicine are the legacy of the Catholic Church in the pioneer territories of the Pacific Northwest—virtually all provided by religious women.

Mention must be made of one outstanding religious woman, Mother Joseph Pariseau, S.P., of the Sisters of Providence. At the invitation of Bishop Blanchet of Nesqually, Mother Joseph and four other sisters headed west and arrived in Vancouver, Washington, on December 8, 1856. Despite enormous hardships, Mother Joseph established more than 30 hospitals, schools, and homes for orphans and the elderly throughout Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana. To honor her, the State of Washington chose Mother Joseph as one of two statues to be placed in Statuary Hall in Washington, D.C.

Archbishop Charles John Seghers

By 1862, Archbishop Norbert Francis Blanchet had moved his residence to Portland, the growing city downriver from Willamette Falls. In 1863, Father J. F. Fierens was appointed pastor of the now “pro-cathedral” in Portland, and he remained as pastor until his death in 1893. In 1878, the old frame church at Third and Stark was taken down, and the cornerstone of a new Gothic pro-cathedral was laid.

As the Catholic population began to increase, the Second Council of Baltimore decided to reorganize portions of the vast Archdiocese of Oregon City. In 1868, the eastern portion of the archdiocese became the Vicariate Apostolic of Idaho (a “vicariate,” administered by a vicar-bishop, precedes a “diocese” in Church law; Oregon City also began as a vicariate in 1843). A Belgian priest, Father Louis Lootens, serving on Vancouver Island, became the first bishop and vicar apostolic of Idaho. When Bishop Lootens arrived in Idaho in early 1869, he found only two priests. The Catholic Church in Idaho was in such dire straits that, in 1876, Bishop Lootens resigned and returned to Vancouver Island. Thus, Idaho returned to the jurisdiction of Archbishop Blanchet, and remained so, until the consecration of Bishop Glorieux in 1885. The Diocese of Boise was erected in 1893.

Archbishop Blanchet celebrated his 50th anniversary of priesthood July 18, 1869, and he marked his anniversary with a letter to his clergy and people. He said that he “hardly expected, in the midst of our long missionary life in hard and incessant labors in this country and elsewhere” to arrive at such an anniversary. In early October of the same year, preceding his departure for Rome and the First Vatican Council, Archbishop Blanchet wrote a pastoral letter in favor of the “infallibility of the Church,” an important topic to be discussed at the council. It is interesting to note that Archbishop Blanchet traveled eastward from San Francisco on the newly completed Transcontinental Railway (1869).

The First Vatican Council opened on December 8, 1869, and it adjourned abruptly on October 20, 1870, when the unification and anti-papal forces captured Rome. Archbishop Blanchet was still in the city during this siege. He returned to Oregon and continued his ministry to a growing population and a complex local church.

By the late 1870s, Archbishop Blanchet, now in his 80’s, was beginning to wind down his active ministry. He requested an auxiliary bishop in 1878, and Bishop Charles John Seghers of Vancouver Island was appointed his coadjutor (i.e., with right of succession).

Bishop Seghers was born in Ghent, Belgium, on December 26, 1839. After completing his studies at a Jesuit college in Ghent, he entered the local seminary. On August 9, 1862, he was ordained a deacon and transferred to the American College in Louvain, Belgium. The American College was founded in 1857 by American bishops to supply North America with English speaking missionary clergy (a similar college was founded in Rome, the Pontifical North American College, in 1859). It was Seghers’ hope to do missionary work in the Washington Territory. Instead, he responded to an appeal by Bishop Modeste Demers to come to Vancouver Island. Ordained a priest on May 30, 1863, Seghers departed for Victoria. For the next ten years, Seghers worked as a parish priest, mostly in Victoria. At the death of Bishop Demers on July 28, 1871, Seghers became the diocesan administrator; and, on March 21, 1873, Pope Pius IX appointed him to succeed Demers as bishop of Vancouver Island.

Much of Seghers’ time was taken up in missionary activities among the various native peoples on Vancouver Island and in Alaska (a part of the island diocese). In 1877, Seghers began a missionary tour along the Yukon River to the Bering Sea. Returning to Victoria after 14 months (through San Francisco), Seghers learned that Pope Leo XIII, on May 6, 1878, had appointed him coadjutor bishop to the ailing Archbishop Francis Norbert Blanchet of Oregon City. When Archbishop Blanchet retired in 1880, he moved to St. Vincent Hospital in Portland, where he spent his final days and wrote his memoirs. Bishop Seghers succeeded him as second archbishop of Oregon City on December 20, 1880.

Archbishop Norbert Francis Blanchet died on June 18, 1883. His death brought to a close an important chapter in the early history of the Catholic Church in the Northwest. The “Patriarch of the West” is buried in the cemetery at St. Paul, Oregon.

Bishop Seghers spent most of the period from 1878 to early 1885 at Oregon City, taking up both administrative and missionary duties in the northwest (at the time Seghers became coadjutor of Oregon City, he was also appointed administrator of the vicariate of Idaho).

In 1885, Jean-Baptiste Brondel, Seghers’ successor on Vancouver Island became the administrator of the new vicariate of Montana, created on March 5, 1883. At that time, Archbishop Seghers, who missed his missionary work on Vancouver Island, received approval from Pope Leo XIII to return to Victoria. On February 10, 1885, Seghers became (again) bishop of the diocese with the personal title of archbishop-bishop.

Seghers was anxious to continue his missionary work in the Alaskan interior, this time accompanied by two Jesuit priests and a layman, Frank Fuller, who had worked at various Jesuit missions. Several colleagues protested Seghers’ choice of Fuller for the missionary journey, concerned about Fuller’s mental instability, but Seghers' decision was made.

Near Nulato, Alaska, Seghers’ first Catholic mission on the Yukon, on the morning of November 28, 1886, Fuller shot and killed Archbishop Seghers.

To replace Seghers in Oregon City, on February 1, 1885, Pope Leo XIII appointed Bishop William Hickley Gross, C.Ss.R, from the Diocese of Savannah, as the third archbishop of Oregon City.

As the Catholic population began to increase, the Second Council of Baltimore decided to reorganize portions of the vast Archdiocese of Oregon City. In 1868, the eastern portion of the archdiocese became the Vicariate Apostolic of Idaho (a “vicariate,” administered by a vicar-bishop, precedes a “diocese” in Church law; Oregon City also began as a vicariate in 1843). A Belgian priest, Father Louis Lootens, serving on Vancouver Island, became the first bishop and vicar apostolic of Idaho. When Bishop Lootens arrived in Idaho in early 1869, he found only two priests. The Catholic Church in Idaho was in such dire straits that, in 1876, Bishop Lootens resigned and returned to Vancouver Island. Thus, Idaho returned to the jurisdiction of Archbishop Blanchet, and remained so, until the consecration of Bishop Glorieux in 1885. The Diocese of Boise was erected in 1893.

Archbishop Blanchet celebrated his 50th anniversary of priesthood July 18, 1869, and he marked his anniversary with a letter to his clergy and people. He said that he “hardly expected, in the midst of our long missionary life in hard and incessant labors in this country and elsewhere” to arrive at such an anniversary. In early October of the same year, preceding his departure for Rome and the First Vatican Council, Archbishop Blanchet wrote a pastoral letter in favor of the “infallibility of the Church,” an important topic to be discussed at the council. It is interesting to note that Archbishop Blanchet traveled eastward from San Francisco on the newly completed Transcontinental Railway (1869).

The First Vatican Council opened on December 8, 1869, and it adjourned abruptly on October 20, 1870, when the unification and anti-papal forces captured Rome. Archbishop Blanchet was still in the city during this siege. He returned to Oregon and continued his ministry to a growing population and a complex local church.

By the late 1870s, Archbishop Blanchet, now in his 80’s, was beginning to wind down his active ministry. He requested an auxiliary bishop in 1878, and Bishop Charles John Seghers of Vancouver Island was appointed his coadjutor (i.e., with right of succession).

Bishop Seghers was born in Ghent, Belgium, on December 26, 1839. After completing his studies at a Jesuit college in Ghent, he entered the local seminary. On August 9, 1862, he was ordained a deacon and transferred to the American College in Louvain, Belgium. The American College was founded in 1857 by American bishops to supply North America with English speaking missionary clergy (a similar college was founded in Rome, the Pontifical North American College, in 1859). It was Seghers’ hope to do missionary work in the Washington Territory. Instead, he responded to an appeal by Bishop Modeste Demers to come to Vancouver Island. Ordained a priest on May 30, 1863, Seghers departed for Victoria. For the next ten years, Seghers worked as a parish priest, mostly in Victoria. At the death of Bishop Demers on July 28, 1871, Seghers became the diocesan administrator; and, on March 21, 1873, Pope Pius IX appointed him to succeed Demers as bishop of Vancouver Island.

Much of Seghers’ time was taken up in missionary activities among the various native peoples on Vancouver Island and in Alaska (a part of the island diocese). In 1877, Seghers began a missionary tour along the Yukon River to the Bering Sea. Returning to Victoria after 14 months (through San Francisco), Seghers learned that Pope Leo XIII, on May 6, 1878, had appointed him coadjutor bishop to the ailing Archbishop Francis Norbert Blanchet of Oregon City. When Archbishop Blanchet retired in 1880, he moved to St. Vincent Hospital in Portland, where he spent his final days and wrote his memoirs. Bishop Seghers succeeded him as second archbishop of Oregon City on December 20, 1880.